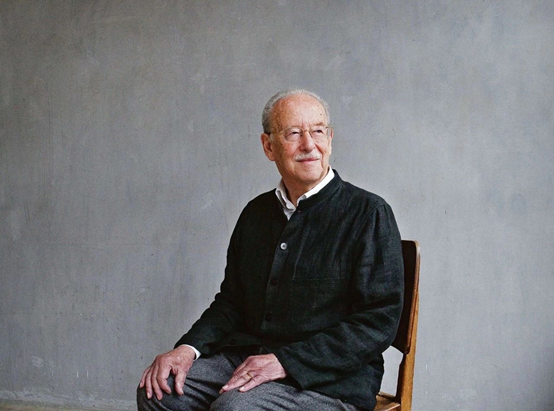

施舟人(1934-2021)

· 勞格文(John Lagerwey)

法國高等研究學院、香港中文大學榮休教授、西南交通大學中國宗教研究中心名譽主任

施舟人老師改變了我的治學之路

我剛得知施舟人教授去世的消息。施舟人教授的研究成果改變了全球漢學的發展方向,也對他的很多學生產生了深遠的影響,包括我在內。

一九七五年底,我從美國來到巴黎從事當時尚未被稱為“博士後”的研究,施舟人教授的課程顛覆了我的很多認識。彼時,我剛在哈佛大學獲得中國古代文學的博士學位,而哈佛還是認為中國歷史上的儒家不是宗教、佛教自唐代便開始衰落、道教是迷信等保守觀點的堡壘。當時關於道教的英文書籍只有尉遲酣(Holmes Welch)的《道家/道教:道之分歧》(Taoism: The parting of the Way),其中提出了傳統的觀點,認為老莊的道家哲學是中華文明的驕傲之一,漢代的道教是離經叛道的形式,是道家式微的標誌。

我在一九七五年到法國是為了師從施舟人和康德謨(Max Kaltenmark)教授進行學習,因為我讀過他們的書,讓我懷疑在哈佛教給我的知識之外,關於中國還有其它可以言說之處。我並未失望,而是恰恰相反,感到無比興奮。一九七五至一九七六年間,我在修讀康德謨關於《太上靈寶五符序》的課程期間,特別是在讀到大禹的神話時,才發現我對自己博士論文的主題《吳越春秋》一無所知。不過,真正轉變我對中國看法的是施舟人在同年開設的兩門課程,即中國宗教导論,以及關於《黃書過度儀》的課,或許還有每週三晚上在施舟人家中對《老子中經》的閱讀,使我明白中國不僅是一個和其它國家一樣的“宗教”國家,而且還產生了自己的高級宗教。對我來說,道教研究從此就成了對中國歷史上“被壓抑的”隱秘篇章的研究。

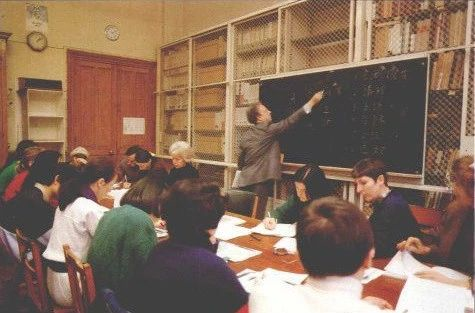

高等研究學院授課中的施舟人

我在法國的第二年又有了其它認識上的衝擊,特別是因為施舟人的“師兄”、臺灣的陳榮盛道長在一九七七年春天來到了巴黎,用閩南語開設了喪葬儀式(功德)和朝科這兩門課程,期間多虧了施舟人的口譯,我由此知道了儀式在道教中至關重要。當時,禮儀還被廣泛地認為是缺乏精神活力的宗教的表現形式,甚至是強迫症心理的表達方式。道教對我的吸引力在於它有望顛覆的不僅有我對中國的認識,還有我年輕時加爾文教的宗教人類學。我個人發生最大的轉變是在一九七七年農曆二月十五,我們在施舟人老師的花園裡舉行了慶祝老君誕辰的儀式,陳榮盛任高功法師,我和范華(Patrice Fava)分別任都講和副講,Brigitte Petit-Archambault和Cécile Léon分別擔任引班和值香。通過這次經歷,我知道我必須全身心地投入於道教儀式的研究之中。

要講的東西還有很多,尤其是關於道藏研究計劃的那段歲月,但我想先通過這篇短文來回顧一下我個人對施舟人老師教誨的感激之情。

(巫能昌 譯,呂鵬志、張粲 校)

原文:

Je viens d’apprendre la nouvelle de la mort de Kristofer Schipper, un homme dont les découvertes ont changé la direction de la Sinologie mondiale, qui a aussi eu un impact hors norme sur ses nombreux étudiants, dont moi-même.

Venu des Etats-Unis à la fin de l’année 1975 pour des études qu’on n’appelait pas encore « post-doctorales », les cours de M. Schipper m’ont bouleversé. Harvard, où je venais tout juste d’obtenir mon doctorat en littérature chinoise ancienne, était encore un bastion de la vision conservatrice de l’histoire chinoise, selon laquelle le confucianisme n’était pas une religion, le bouddhisme était sur le déclin depuis les Tang et le taoïsme était de la superstition. Le seul livre en anglais qui existait à l’époque sur le taoïsme était celui de Holmes Welch, Taoism: The parting of the Way, où il avançait l’argument traditionnel que le taoïsme philosophique de Lao-Zhuang était une des gloires de la civilisation chinoise, le taoïsme religieux de l’époque Han une forme déviante, signe de déchéance.

Si je suis venu en France en 1975, c’était pour étudier avec Schipper et Max Kaltenmark, car j’avais lu leurs livres et me doutais qu’il y avait autre chose à dire de la Chine que ce que j’avais appris à Harvard. Je n’ai pas été déçu, bien au contraire, j’ai été bouleversé. En suivant le cours de M. Kaltenmark, qui portait en 1975-76 sur le Taishang lingbao wufuxu, surtout en lisant le mythe de Yu le Grand qui s’y trouve, j’ai compris que je n’avais rien compris au sujet de ma thèse, le Wu-Yue chunqiu. Mais ce sont les deux cours de M. Schipper en cette même année – l’une d’introduction à la religion chinoise, l’autre sur le Huangshu guoduyi – et peut-être encore plus la lecture hebdomadaire que je faisais tous les mercredi soirs chez lui du Laozi zhongjing qui ont vraiment transformé ma vision de la Chine : non seulement la Chine est-elle un pays « religieux » comme tous les autres, elle a produit sa propre religion supérieure. Dès lors, pour moi, l’étude du taoïsme religieux devenait celle du chapitre « réprimé » - occulté – de l’histoire chinoise.

Ma deuxième année en France a apporté d’autres bouleversements, notamment à cause de la venue, au printemps de 1977, du « frère » de Schipper, le maître taoïste Chen Rongsheng de Taiwan. C’est par ces deux cours en langue Minnan, sur les rites funéraires et sur le rituel d’Audience, que j’ai appris – grâce aux traductions orales que faisait Schipper pendant les cours – le caractère central du rituel dans le taoïsme. A une époque où les rites étaient encore largement considérés comme des formes d’une religion spirituellement inerte, voire comme des expressions de psychologie obsessionnelle, l’attrait du taoïsme pour moi était sa promesse de renverser non seulement ma vision de la Chine, mais aussi l’anthropologie religieuse du calvinisme de ma jeunesse. Ce moment de transformation personnelle a trouvé sa plus marquante expression dans le jardin de Kristofer Schipper, où, avec Chen Rongsheng en Gaogong, moi et Patrice Fava en cantors et Brigitte Petit-Archambault et Cécile Léon en préposées aux processions et à l’encens, nous avons célébré l’anniversaire de Laozi au quinzième jour du deuxième mois de 1977. Je savais, après cette expérience, que je devais me consacrer tout entier à l’étude du rituel taoïste.

Il y aurait bien d’autres choses à raconter, en particulier sur les années du Projet Daozang, mais je voulais, par ce premier jet, rappeler ma dette personnelle à l’égard de l’enseignement de Kristofer Schipper.

· 傅飛嵐(Franciscus Verellen)

法國遠東學院道教史教授、法蘭西學院銘文與美文學院院士、香港中文大學中國文化研究所高級研究員

紀念施舟人教授

道教研究泰斗施舟人教授(Kristofer Marinus Schipper, 1934-2021)於2021年2月18日在阿姆斯特丹溘然長往,享年86歲。施舟人曾供職於法國遠東學院,他在1962至1970年間對臺灣鮮活的道教科儀傳統進行了田野考察。無論是在中國還是在西方學界,這些工作在半個世紀以來滋養了關於“中國高級宗教”的研究,改變了我們對華人世界宗教生活的理解,革新了漢學研究的相關領域。

施舟人還是荷蘭皇家科學院院士、萊頓大學榮休教授、法國公學高等研究學院榮休教授、法蘭西學院高等漢學研究所所長(1987-1992),以及法國國家科研中心“道教文獻目錄提要”(1979-1985)和“聖城北京”(1996-1999)這兩個研究團隊的負責人。

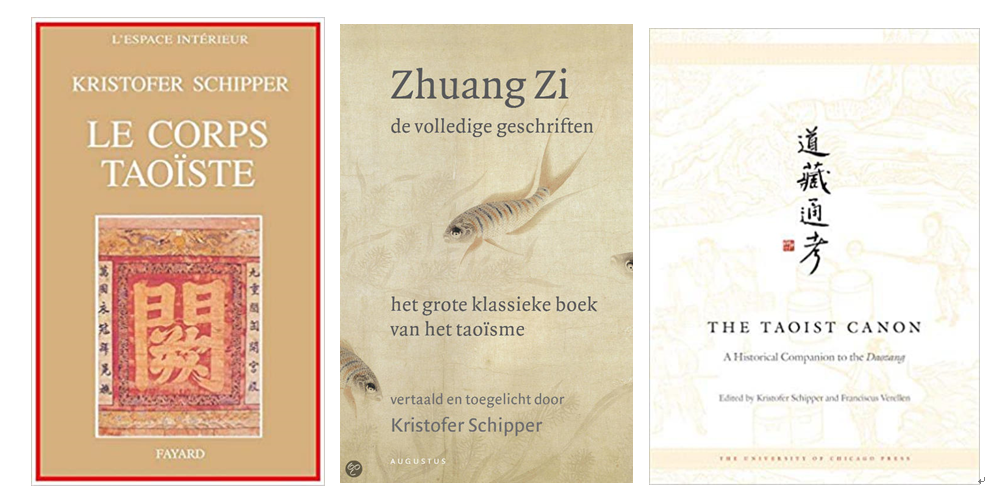

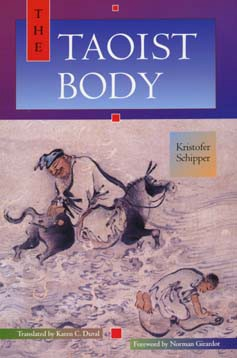

施舟人培養了好幾代的中國宗教研究學者,其中許多人至今仍繼續傳承著其遺產。其開創性的工作充滿了不可替代的深刻見解,奠定了很多最成功的國際研究項目的基礎。除了在道教典籍和科儀方面的開拓性研究,他還著有《道體論》(Le corps taoïste)和《中國宗教》(La religion chinoise),給漢學界貢獻了最好的道教概論,並成功地發起編撰集體著作《道藏通考——明道藏經歷史指南及解題目錄》。此外,不要忘記他還用荷蘭語譯註了《莊子》全文,以及他在生命的最後時光傾力而為的事情。

施舟人離開了其妻子袁冰淩和他們的女兒Maya,前妻Wendela和他們的兩個女兒Esther和Johanna,以及幾個孫輩。漢學界失去了一位偉大的學者,而曾經有幸和他共事的人則失去了一位無與倫比的同事和朋友。

(巫能昌譯 呂鵬志、張粲校)

原文(法文版)

In Memoriam Kristofer Schipper

Le maître et le doyen des études taoïstes Kristofer Marinus Schipper (1934-2021) s’est éteint soudainement le 18 février 2021 à Amsterdam, à l’âge de 86 ans. Ancien membre de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient, Kristofer Schipper mena à Taiwan entre 1962 et 1970 les travaux de terrain sur la tradition liturgique vivante du taoïsme qui devaient nourrir un demi-siècle de recherches fondamentales sur « la haute religion de la Chine », transformer notre compréhension de la vie religieuse dans le monde chinois et rénover tout un pan des études sinologiques, tant en Occident qu’en Orient.

Membre de l’Académie royale néerlandaise des arts et des sciences, professeur émérite de l’université de Leyde, directeur d'études émérite de l’École pratique des hautes études et ancien directeur de l’Institut des hautes études chinoises du Collège de France (1987-1992), Kristofer Schipper fut responsable de deux groupes de recherche du CNRS : « Bibliographie taoïste » (1979-1985) et « Pékin ville sainte » (1996-1999).

Kristofer Schipper forma plusieurs générations de spécialistes des religions chinoises, dont nombre continuent à transmettre son legs aujourd’hui. Fourmillant d’intuitions irremplaçables et perspicaces, ses initiatives furent à l’origine de nombre de projets internationaux de recherche des plus fructueux. Outre ses travaux pionniers sur les textes et les rites taoïstes, la sinologie doit à Kristofer Schipper les meilleures présentations générales pour le taoïsme, à savoir Le corps taoïste et La religion chinoise ainsi que sa contribution essentielle à l’ouvrage collectif The Taoist canon, l’analyse historique et bibliographique du vaste canon dont il prit l’heureuse initiative, sans oublier la traduction complète et annotée du Zhuangzi, en néerlandais, et passion des dernières années de sa vie.

Kristofer Schipper laisse son épouse Yuan Bingling et leur fille Maya, ainsi que l’épouse d’une première union, Wendela, leurs deux filles Esther et Johanna, et plusieurs petits-enfants. La sinologie perd un immense savant, et ceux qui ont eu l’avantage de le côtoyer, un collègue et ami hors pair.

英文版

IN MEMORIAM KRISTOFER SCHIPPER

The doyen of Daoist studies Kristofer Marinus Schipper (1934-2021) passed away in Amsterdam on February 18, 2021, aged 86. As a former member of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (1962-1972), Kristofer Schipper carried out fieldwork on the living liturgical tradition of Daoism in Taiwan that would launch half a century of path-breaking research into “China’s high religion,” transform our understanding of religious life in the Chinese world, and foster new approaches to the study of Chinese religion and society in East Asia and the West.

A member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Kristofer Schipper was director of the Institute of Chinese Studies, Collège de France, from 1987 to 1992. As professor of Chinese History at the University of Leiden and professor in the History of Daoism at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris, he trained a generation of specialists in Chinese religion, many of whom carry on his legacy today. His unending supply of far-sighted intuitions was at the origin of some of the most fruitful international research projects in recent years.

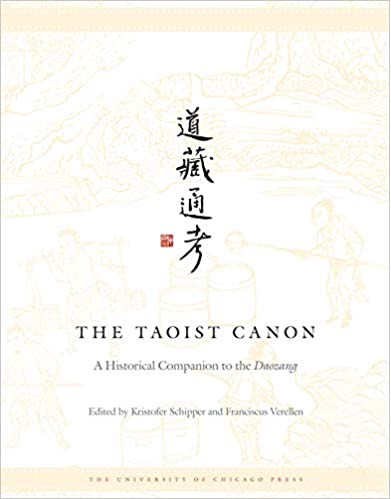

In addition to countless specialist studies on the ritual and text traditions of Daoism and his essential contributions to The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang (University of Chicago Press, 2004), the most ambitious project he initiated, we owe Kristofer Schipper the most comprehensive introductions to Daoism in The Taoist Body (trans. Karen C. Duval, University of California Press, 1993) and La religion de la Chine: la tradition vivante (Fayard, 2008), not to mention a complete translation into Dutch of the Zhuangzi, one of his absorbing interests in later years (Zhuang Zi, De volledige geschriften, Uitgeverij Augustus, 2007).

Kristofer Schipper leaves behind his wife Yuan Bingling, their daughter Maya, and his wife and two daughters from a first marriage. The field of Chinese religion has lost a pioneering scholar and an inspiring teacher, those who were privileged to know him and work by his side, a rare friend and colleague.

Franciscus Verellen

· 柏夷(Stephen R. Bokenkamp)

美國亞利桑那州立大學教授、西南交通大學中國宗教研究中心學術委員會主任

In memoriam Kristofer Marinus Schipper, 1934-2021

When I first learned of the passing of Kristofer Marinus Schipper, like anyone experiencing the death of an acquaintance – an all too frequent occurrence for all of us recently -- I felt a sinking pain in the solar plexus. Flee or hide?

Gradually, the reality began to sink in and my thoughts were flooded with images: Professor Schipper (I could never call him “Rik”) in Tokyo, 1985 or so, telling me earnestly that I should…I forget what it was, but it was probably good advice and I hope that I followed it; or at the first Chinese-sponsored international Daoist Studies conference in Beijing, 1996 — an event cautiously titled symposium on “Daoist Culture,” spelled道家文化 (no Daoists here!) — when, at the banquet on the last night when the Korean contingent, it being National Liberation Day, sang a patriotic song and the Japanese group was starting to act offended, Schipper took the microphone and, beating time on it with a chopstick, sang a Taiwanese Daoist hymn, calming everyone down and reminding us why we were there; or at some conference in Shanghai, where I first met his daughter Maya, I think she must have been five or so at the time; or the same secret pride I could see emanating from him at our gathering at Aussois. These and other images have been swirling through my heart and head for days now. It might be actually how 白日昇天actually happens. But then I remembered the words of Lü Dongbin that Schipper himself cited: “If you see the Master, dismiss him from your mind.”

Everyone who knew the man will have their own Professor Schipper with them until they too become ascendant, so that is likely good advice. My Professor Schipper is not yours. But what I want to try to communicate in this note is something about this man that is even more rare on this earth and worthy of commemoration than the individual memories we all have.

There are only a few scholars, very few, maybe one in a generation, who are able to survey the lineaments of a field of study and discern the possibilities that lie hidden in directions not taken. Often those directions themselves are open to view in afterthought, plain on the ground.

I am thinking of feats of the scholarly imagination that changed the world, like what George Lyman Kittredge did for the collection of American ballads and folklore and their comparison with the songs of their European and African places of origin. Or what Albert B. Lord accomplished through connecting the composition practice of Serbian folk minstrels with the epics of Homer and the unknown authors of Beowulf.

Schipper’s accomplishments we all know…or should: his fieldwork in Taiwan in the 60s; his numerous pathbreaking publications; his sponsorship of the Projet Tao-tsang and the eventual publication with Franciscus Verellen of the important The Taoist Canon; the many leaders in Daoist scholarship whom he trained. But I would want us to remember the insight that made all of these things possible. Though it sounds simple in the many formulations Professor Schipper gave it, it is a brilliant inspiration concerning what is important in Chinese culture. The call reverberates throughout Professor Schipper’s work and teaching. Vincent recalls for us one formulation: it is important not to forget “the Other China,” the “Real China” as expressed in the traditions and customs of the people -- often through Daoism, that is. Another way he put the same inspiration was instrumental in helping to secure funding for the Projet Tao-tsang: “Daoism is part of the world cultural gene bank,” “something too important to be left to the Chinese people alone.”

It is fascinating to me, now that I have dismissed the vision of the Master from my mind for a bit, the better to hear him, how this startling insight that, say, the Daoist Masters working among the people in Tai-nan might represent the important treasures of a culture more accurately than thousands of editorially-altered books, seems so apposite to the rustic things that Kittredge and Lord and other geniuses took as their fields of study. We make things too difficult for ourselves sometimes. Professor Schipper leads us to a consideration of what is to be found in the quotidian, the unremarked, or the repressed where we live our lives. Thank you, Professor Schipper.

Stephen R. Bokenkamp

27 February 2021

· 呂錘寬

泉州師院閩江學者講座教授、台灣師範大學退休教授

悼念施博爾教授

日前從呂鵬志教授處得知,道教科儀研究的權威施博爾教授仙逝,特為文將與他的接觸所獲得學術上的啟發與收穫,撰述為文以表悼念之情。

最初知道施博爾的名號,係在臺南的南管文化圈,南聲社的絃友們皆稱他為“阿博”。背景原因為:施博爾教授於 1960 年代到臺灣,隨即前往臺南向陳聬道長學習靈寶派的科儀,期間也致力蒐集臺灣傳統音樂的有聲資料,他從唱片中獲知,臺南南聲社有一位傑出的演唱者蔡小月,因而專程於 1981 年前來臺南,為法國廣播公司洽談聘請蔡小月等,赴法國等歐陸五個國家的演出,最後確定於 1982 年 10 月邀請蔡小月與南聲社前往演出。施博爾教授的名聲,乃在以臺北為主的文化界與音樂界傳播開來而廣為人知。

本人起始係研究南管音樂(本稱為絃管,為保存於泉州晉江等地的古樂),於1984 年獲得法國政府獎學金,前往巴黎索邦大學(Université Paris-Sorbonne)音樂學院就讀,當時的博士研究論文為南管音樂方面,故而指導教授之一即為施博爾教授,因此在巴黎一年期間,大抵為每星期到他家討論,才初次認識建醮與道教科儀,及宣行的相關文化現象。

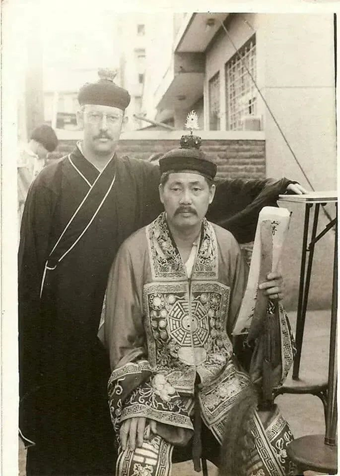

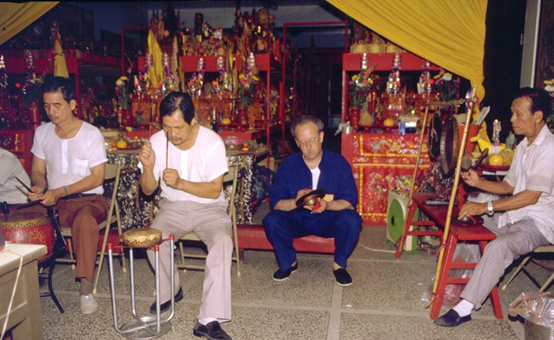

作者和施博爾教授的合影

1985 年 12 月,陳榮盛道長於臺南縣七股鄉九龍宮主持一科三朝醮,施博爾教授特地前來實地調查,他到臺南都會拜訪南管演唱家蔡小月,由於本人與蔡小月為結拜關係,故而乃相約前往陳榮盛道長的法事道場探訪,這也是本人第一次見識到蘊含豐富傳統音樂的傳統文化場域,也得以知施博爾教授與道士、樂師熟識以及親密的關係。1991 年 6 月,陳榮盛主持臺南縣西港鄉慶安宮醮典,施博爾教授仍特地前往,且於朝科中擔任都講職,夜間的鬧壇奏樂,且拿著銅類樂器參與演奏,親眼目睹他一方面既熟識道教的人事,且對科儀本體仍有實際操作執行的能力。

施舟人教授與陳榮盛道長

從學術眼光言之,施博爾教授堪謂為本人在道教科儀與音樂方面研究的啟蒙老師,在他家討論期間,因而有機會瞭解道教的相關文獻,以及他從臺南蒐集的手抄本的類型,諸如有:科儀書、文檢、玉訣、雜記等,這些認識或概念,儼然為後續的道教科儀研究的指引。

1990 年第二次到巴黎,此次係註冊於 École Pratique des Hautes Études,註冊的論文題目為道教早朝科儀方面的研究。除了進一步瞭解施博爾教授在道教科儀方面的造詣,在巴黎期間,另一方面見識到他與民間藝師熟悉的程度: 1990 年 11月,他再次引介法國國家廣播公司,聘請蔡小月與南聲社至巴黎演出與錄音,將蔡小月所能的南管曲全部予以錄音,日後並發行一套六片的“蔡小月南管曲專輯”CD;1991年12 月,再次聘請陳榮盛道長至巴黎講授道教科儀,期間施博爾教授並邀請陳道長前往阿爾卑斯山賞雪,由本人為陪賓,因而能有機會更深入認識施博爾與道士的關係,以及他的思想與見解。

從耳聞至認識以及實際接觸施博爾教授的過程,除了具體吸收他在道教科儀方面的研究方法與觀念,最重要者為經由對他的觀察獲得的啟發,亦即學術研究的實務經驗,此經驗係從不斷的田野調查而來,實際情形為持續保持與臺南道士的密切關係,而非為輾轉抄襲引用的歷史材料或空談的理論。

施博爾教授在道教科儀方面研究的成果,為歐美漢學界熟知與推崇,對歐洲社會而言,他對漢族傳統音樂中的南管音樂之提倡,成為法國藝文界的盛事,顯示他生前在道教科儀研究的成就,以及倡導漢族傳統音樂的貢獻。親眼所見,他仍為富於情感的學者,陳榮盛道長於 2015 年過世的時候,亦專程到臺南參加告別式。施博爾教授在臺南學習道教科儀、傳播南管音樂的事蹟,已成為臺灣道教文化圈與傳統音樂文化圈的美談。

作者在施博爾教授家(1985年)

施博爾教授鬧壇演奏(1991年)

施博爾教授科演(1991年)

· 葉明生

福建省藝術研究院研究員

忆与施舟人教授的一段学术情缘

19日,驚悉施舟人教授仙逝的消息,心裡十分難過,使我想起一段與施教授接觸之往事,撰寫出來,以表我的悼念之情!

1990年中秋節的一天,我還在壽寧老家的縣文化局工作時,法國遠東學院的勞格文博士到壽甯山鄉訪問我,跟我談起在國內做道教文化田野調查事,希望得到我的配合。從他的自我介紹,我得知其老師是法國著名道教研究泰斗施舟人(施博爾)教授,知道他當時還在臺灣從事道教文化研究。在勞格文給我的資料中就有幾篇施先生的大作,我從此開始關注施教授道教研究的方向、方法和經驗,在1991年受聘於臺灣清華大學“中國地方戲曲與儀式研究”課題項目期間大有受益,使我在臺灣著名民俗學專家王秋桂先生主編的《中國傳統科儀本彙編》叢書中大展身手,順利完成出版《福建省龍岩市東肖鎮閭山教廣濟壇科儀本彙編》《福建省建陽市閭山教科儀本彙編》《福建省壽寧縣閭山梨園教科儀本彙編》,以及後來的《閩西南永福閭山教傳度儀式研究》等道教相關著作。1994年起,我應臺灣清華大學王秋桂教授邀請,多次赴臺參加有宗教、民俗與儀式戲劇等方面的學術研討會,曾望有機會拜訪施教授並當面請教,但因行程倉促,均以未能實現為憾!

2002年9月26日,在參加古田縣舉辦的“第二屆閩台臨水夫人陳靖姑文化學術研討會”上,我於意外之中終於見到了施教授,並聆聽他精深的學術報告《從外國人的角度看臨水夫人信仰及其在世界文明的地位》,還得知施教授和袁冰淩博士已從臺灣移居福州,受聘於福州大學。這次研討會最引人注目的話題是施舟人教授的發言,其中說道:“陳靖姑文化是中國宗教女神文化的一個代表,有別於世界其它幾大宗教,在道教的歷史上,臨水夫人是第一個來拿起武器打擊妖魔、幫助祖國、拯救黎民的女神。不僅如此,為了解救面臨嚴重自然災害的閩國,臨水夫人脫胎求雨,犧牲了自己的胎兒,最後也奉獻出了自己年輕的生命。這種極其英勇的行為在歷史上十分罕見的。在其它宗教中,只有十五世紀(相當於明正統年間)法國的聖女貞德(Joan of Arc)可以與臨水夫人相比。”

施教授的發言於會引起極大反響。我在會上的發言為《福建道教女神陳靖姑信仰文化研究——“夫人教”在中國南方的流播及影響》。其中較為詳盡地介紹了由陳靖姑信仰及其衍化的“夫人教”在湖南、江西、浙江、廣東、臺灣的流行情況,並就夫人教研究的意義進行了闡述,強調臨水夫人信仰和夫人教在南方傳播的廣泛性。我的發言深得施教授讚賞,會後他真誠約我到福州大學見面。

2003年9月,受施教授之邀,我到施教授家中作客,他對我堅持民間道教的田野調查稱讚有加,並鼓勵我系統瞭解道教儀式的傳承和衍變特徵,並加以深入調研。10月20日,我應邀參加福州大學建校45周年及該校人文社科院成立暨西觀藏書樓開幕系列學術講座。安排我兩小時的講座命題為《福州地區的臨水夫人信仰與夫人教》,施教授親自主持我的講座,並對我的講座給予點評,除了給予很高的評價,同時也對有些問題進行商榷,並鼓勵在場師生在道教與民間信仰田野調查方面向我學習,使我深受鼓舞。後來施教授移居北京,再後返回荷蘭故鄉,我們一直無緣再會。但是在這後來二十年的歲月中,他使我在後來的研究道路有了更明確的目標和方向。與施教授這段情緣一直使我難以忘懷。我們將永遠懷念這位擅於提攜後生晚輩之德高望重的道教學研究泰斗!

· 高萬桑(Vincent Goossaert)

法國高等研究實踐學院(EPHE)宗教學系道教史講座教授

但開風氣不為師——紀念施舟人教授

很少有人像立科(Rik,即 Kristofer M. Schipper 施舟人教授)那樣改變了中國宗教研究領域,同樣很少有人像他那樣改變了我的生活。會有很多緬懷他的正式悼文,不過請允許我從個人的角度來寫一些文字。立科是一個非凡而難以捉摸的人,我們可以從很多方面來介紹其獨特的性格。對我來說,他是慷慨的化身:不僅僅是在金錢方面(他當然也是這樣),而是在包括時間、想法、書籍等等的一切方面。他就是有很多東西可以分享。

第一次去見他的時候,我還只是個好奇的商學院學生,沒有任何資格去讀道教研究方面的博士。一個謹慎的教授會對我說:“先去學三年文言文和兩年歷史吧,然後我們再談。”他卻沒有這樣,只是信任我,於是我馬上就開始了。他在我的求學之路上設置了一些高難度的障礙,讓我明白這是一件嚴肅的事情,但在關鍵時刻總會讓我非常確定地明白他是真的關心我,就像對很多其他的學生一樣。1990年代,我在立科萊頓的家中度過了不少時間,我們一起做飯,整夜整夜地交談,他的藏書也供我使用。我會永遠珍惜這些日子。他不求回報,只是希望能有充滿激情的人去探索他為我們開闢的領域——“另一個中國”(或“真正的中國”)。一個年輕人如此强烈地感受到道教之美讓他感到高興。我畢業之後,他為我爭取到了去荷蘭做博士後研究的面試機會,並把他最好的西裝給我穿,讓我看起來很不錯(西裝不是我的菜……);我得到了這份工作,但隨後就被法國國家科研中心錄取,獲得了更好的職位。每當他的學生取得一些成功時,他都會很高興,而總而計之,可謂碩果累累。

和立科一起度過的研究生時代是非常美好的回憶。他的研討課在週六上午的10到12點,開設於索邦大學,大家圍著一張巨大的木桌。很遺憾的是,這張木桌後來就沒有再見到過了。他帶來了文獻,讓我們一起閱讀:各種文獻,如高道傳記、《莊子》、他自己的科儀抄本(尤其是在最後的1999-2000學年)。他抑揚頓挫地朗讀文言文,並進行翻譯、解釋和評論,但著意捕捉我們自己的見解。他是一個睿智的人,但很註意我們要說的話。到了中午12點,我們離開索邦的老校區,前往一家意大利餐館共進午餐。對於我們這些幸福的少數人來說,這是知識盛宴的愉悅延續,而且是以更實質的形式——作為一個真正的道士,他非常喜歡美食。

立科是如何教導和啟發學生的呢?多年來,我已經習慣於將他比作富有遠見、能在許多人僅看到事實之時就洞察深層模式的數學家。他經常提出大膽甚至驚世駭俗的觀點,他向來都這樣,而且隨著年齡的增長愈發如此。較為沉著的漢學家會把這些觀點撇開,說沒有證據。我們中間比較好奇的人則會接受提示,並在這方面下功夫,總是卓有成效。立科自己也是這樣做的,他的文獻學功底極好,能用所有最精微的細節來表達令人信服的觀點。不過,他的想法見解甚多,無法獨自一一研究著述,於是就和大家分享。我寫的書中有幾本基本上都源於他說過或寫過的幾句話,是對這些見解研究探索的最終結果。拙著《中國的牛禁》(L’interdit du bœuf en Chine, 2005)就是和他一起做飯的副產品。他有些最初的想法可能實際上是錯誤的,但這無關緊要,因為它們開闢了全新的研究領域和思考方式。僅僅是探索研究它們就足以令人振奮,拓寬思路,這是任何一個老生常談的話題都無法達到的效果。而且在他留下的提示中,無疑還有更多的東西有待探索。

立科是無法效仿的,我們每個人都要找到自己成為一個大學者,或是偉人的最佳路徑。但我當然希望有朝一日能像他那樣慷慨和文思泉湧。他在艰難的環境和條件下,從其父母和義父一家那裡學到了慷慨和傳承之道。如今,這個最可貴的重任落在我們身上,輪到我們來擔當和傳承了。

2021年2月25日

(巫能昌譯 方玲校)

作者和施舟人教授(譯者攝於法國遠東學院,2015年)

原文

Very few people changed the field of Chinese religions as Rik did. And, very few people changed my life as he did. There will be many formal tributes and obituaries, but please bear with me as I write something on the personal side. Rik was extraordinary and unpredictable, and his unique persona can be presented in many ways. My own way of remembering Rik is that he was generosity incarnate: not just with money (he certainly was that too), but with everything: time, ideas, books, everything. He just had so much to share.

When I first came to meet him, I was just a curious business school student, without any of the credentials to do a PhD in Daoist studies. A careful professor would have said “First do three years of classical Chinese and two of history, and we’ll talk.” He didn’t; he just trusted me, and I started right away. He set some high hurdles along the road, so that I understood this was serious business, but at key moments, he made very sure I understood he really cared for me, as he did with so many other students. I spent quite a few days and nights at his house in Leiden in the 1990s; we cooked together, we talked for nights on end, his library was mine to use. I’ll treasure these days forever. He did not ask for anything in return; he just wanted passionate people to explore a land he had opened for us – the “other China” (or “Real China”). That a young person felt so strongly about the beauty of Daoism made him happy. After I graduated, he secured me an interview for a postdoc position in the Netherlands, and gave me his best suit to wear so that I looked good (suits are not quite my thing…); I got the job but just afterwards got an ever better position at CNRS. He was happy as he was whenever one of his students scored some success, which in the end amounts to a lot.

The graduate days with Rik are a very sweet memory. His seminar was on Saturday morning, 10-12am, in the Sorbonne, around the huge wooden table that has since – very sadly – gone. He brought texts for us to read together: everything, hagiography, Zhuangzi, his own liturgical manuals (especially during the last year, 1999-2000). He read, in beautiful-sounding wenyan, translated, explained, and commented at length, but he tried to extract our own insights. He was witty, but attentive to what we had to say. Then, at 12am, we moved out of La vieille Sorbonne, and into an Italian restaurant. And for the happy few this was a happy continuation of the intellectual feast, now together with more substantial fare as well – which as a true Daoist, he loved to the full.

How did Rik teach and inspire students? Over the years, I have taken to compare him to visionary mathematicians who clearly see deep patterns where many others see factual fog. He often – and this, while always there, became more and more prevalent as he grew older – pronounced bold, occasionally outrageous claims. The more sedate sinologists would brush them aside, saying there was no proof. The more curious among us would take the hint and work on it, always fruitfully. Rik himself did that too: he was extremely good with the philological skills, and could make a compelling point with all the finest details. But his insights were too many for him to tackle alone, outpouring to no end, so he shared them. A couple of my books are basically the end result of exploring a couple sentences he said or wrote. My Chinese beef taboo book (2005) is a side-product of cooking dinner with him. Some of his initial statements may have been factually wrong – which does not make any difference whatever: they opened entirely new territories, new ways of thinking. Just exploring them was exhilarating and mind-opening in a way no beaten-track topic can be. And, be assured, there is much more left to explore among the hints he left.

There is no imitating Rik and each of us has to find out her or his best way to be a great scholar and a great human being. I certainly wish I could one day be as generous and outpouring as he was. He had learnt – the hardest way – about generosity and transmission from both his native and adoptive families. This most precious burden in on us now is to assume this generosity and transmit it in turn.

· 祁泰履(Terry Kleeman)

美國科羅拉多大學東亞語言與文學系教授

I arrived in Paris on Bastille Day, 1986. I was, to be honest, a bit bewildered, a new father with a 4 month-old daughter in tow, blundering into an intricate and tradition-bound academic culture with poor French and little international experience. From the beginning, Professor Schipper recognized the challenges of my “year in Paris” and did all he could to ease my way. In addition to his seminar at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, we met weekly in his home on rue Hallé, reading through the text of the Book of Transformations 文昌化書 chapter by chapter in front of his immense altar of gods. His insightful comments on passage after passage opened my eyes to how this text was tied to daily practice and interwoven with Chinese society, transforming my understanding of a religion to which I had already dedicated a decade of study. I noted then how Rik was concerned with the personal lives of his students, more like a Chinese 老師 than a Western professor, and when I had a falling out with my advisor over my plans, he was there to support me and show me a way forward. Our entire field has been shaped by his scholarship, indeed, it is hard to imagine the field without him, but I will always be most grateful for my year of tutelage at the feet of the master.

Terry F. Kleeman

Exchange student at EPHE, 1986-87

· 呂鵬志

西南交通大學人文學院教授、中國宗教研究中心主任

旁聽施舟人先生授課紀念

驚悉西方道教研究權威施舟人教授仙逝於荷蘭阿姆斯特丹,不勝悲痛。回想起我2002年初次留學法國,有幸聆聽施先生榮休前最後一個學年講授道教與中國宗教課程,受益頗多。其間曾蒙施先生開車帶我到他的荷蘭家鄉遊玩幾日,得以有機會討教許多具體問題。為了學習和了解施先生的成果和方法,我在法國高等漢學研究所圖書館複印了他的所有作品,包括未刊會議論文。還複印了《高等研究學院年鑑》(Annuaires de l’École pratique des hautes études)所載1972-2002三十年間施先生所有課程紀要,經常翻閱,後來我在香港中文大學和西南交通大學開設了一系列道教課程,就部分得益於施先生的啟發。

2001-2002學年施先生為高等研究學院開設兩門課程,一門是“從韋伯、高延迄今中國研究的宗教社會學”(“La sociologie religieuse de la Chine, de Weber et de Groot à nos jours”),非漢學專業的學生也可以旁聽。另一門是“《正一法文》與第一個道教教會”(“Le Zhengyi fawen et la première église taoïste”),要求聽課者古漢語基礎較好。兩門課程都是半個月一次,集中在週四同一天進行,但上課地點不同,分別安排在巴黎北部的“宗教社會學和世俗化研究組”(法國國家科學研究中心與高等研究學院聯合研究組)和巴黎東部的“亞洲之家”(法國遠東學院總部所在地)。施先生上課非常辛苦,因為他平時住在荷蘭家鄉,上課那天必須早晨四、五點就起牀,從家鄉乘高鐵趕到巴黎上課。上午從11時講到午間13時,中午簡單午餐後就匆匆趕去講下午的課,從15時一直講到17時。

第一門課講西方學者如何用宗教社會學的理論和方法研究中國宗教,課堂上分發的參考資料是弗里德曼(M. Freedman)為葛蘭言《中國人的宗教》英譯本(The Religion of the Chinese People)寫的導論,此書被弗里德曼視為凃爾幹一系(Durkheimian)社會學的重要著作。施先生不是照本宣科,完全撂開書本講授,不急不慢,娓娓道來。他要講的知識太多了,這門課基本上是“一言堂”,並不安排討論發言。聽眾頗多,老中青都有,大家都聽得很專心,表現出非常享受的神態。施先生講話風趣幽默,時不時就看到聽眾被逗笑。我法語聽力不好,好多笑話都沒聽懂,聽講理論更是騰雲駕霧,但也有不少收穫。一是切身感受到施先生學問淵博,教學有方,對後輩學人影響巨大。我親眼得見,課堂上認真聽講且聽到精彩處會心微笑的同輩學友高萬桑(Vincent Goossaert)、宗樹人(David A. Palmer)、汲喆後來都成長為中國宗教研究領域的著名學者,三位都特別擅長運用宗教社會學的方法。二是初步認識到宗教與社會關係密切,宗教社會學的觀念有助於我們更加深刻地理解被視為東方神秘主義的道教。我注意到,施先生綜括論述道教的名著《道體論》(Le corps taoïste,直譯為“道教的身體”)有一個副標題“人的身體,社會的身體”(Corps physique, corps sociale,或譯為“肉身,社會之身”,與晉代高道葛洪《抱朴子內篇》所謂“一人之身,一國之象”的說法相似),可能正是施先生從宗教社會學角度對道教實質的精闢概括。此書也讓我逐漸懂得,道教儀式是形象地反映中國人與自然(宇宙)、社會之關係的“活化石”,值得花大力氣去研究。我當年很快決定半路出家鉆研道教儀式,最近還在負責籌備“道教儀式與中國社會”國際學術研討會,可以說與施先生的影響不無關係。

第二門課講早期天師道的信仰、實踐和儀式,課堂上分發的閱讀材料主要是天師道經典《赤松子章曆》。施先生總是先講一些有關天師道的知識點,然後指導大家讀《赤松子章曆》中的相關段落。這些知識點主要來自他頭一年在《高等研究學院年鑑》發表的法文論文《道教的清約》(“Le pacte de pureté du taoïsme”),此文也由施先生本人於當年譯成中文,刊載於中華書局出版的《法國漢學》第七輯“宗教史專號”。令我感受特別新奇的是,他用“土洋結合”的方法指導大家閱讀道經。他先用普通話一字一句唸完一段文字,抑揚頓挫,頗注意字音和停頓,像是在口頭標點,然後用法語逐字逐句翻譯和講解。可能為了提高聽課人員的注意力或測試各位是否讀懂,施先生凡讀到疑難詞句(如天師道章文末尾的“以聞”二字)總喜歡問是什麼意思,而且經常點名提問。可能因為天師道經典辭約旨隱,很不好懂,通常是無人應答,被點名者都是搖頭。但輪到我,則十有八九能夠正確回答。一則因為我留學法國之前完整抄錄了五十多部漢唐天師道經典,對天師道經典非常熟悉;二則因為我翻譯過天師道專家傅飛嵐(Franciscus Verellen)的英文論文《天師道上章科儀——〈赤松子章曆〉和〈元辰章醮立成儀〉研究》,對《赤松子章曆》也很瞭解;三則因為手持道經原文聽施先生用法語翻譯,像看有字幕的法語電影,基本都聽懂了。施先生很滿意我的回答,在課堂上表揚我“全知道”,令我深受鼓舞。聽了施先生的授課,我對天師道的理解更加深入,後來發表了十多篇考論天師道儀式或相關道教儀式的論文,每篇2-9萬多字。施先生這門課不只惠澤我的研究,也影響了我的教學。我在西南交大也採用“土洋結合”的辦法,要求哲學所研究中國宗教與中國哲學的研究生選修或旁聽中文系開設的古典文獻學課程,訓練研究生點校、註釋和翻譯古代道書的能力,同時要求他們參閱相關外文譯註或論著,促使他們真正讀懂並透徹理解原始文獻。我上課經常要求預習的同學朗讀幻燈片上引用的古書原文,請他們解釋或白話翻譯其中的疑難詞句。新冠疫情期間,我聯合校內外專家學者共同開設了“道教儀式”“中國宗教文獻”兩門網課,並嘗試在網課中推行我的教學方法。兩門網課都取得了很好的效果,迄今海內外參與兩門網課的聽眾已近八百人次,反響熱烈。只有我心裡知道,這是施先生言傳身教的遺響。

竊以為,我們這一代道教學人,幾乎無不受惠於施舟人教授的博大學問。我個人並代表西南交通大學中國宗教研究中心全體同仁在此表達深切悼念,願施先生流芳百世,永活在我們的懷念裏!

· 宗樹人(David A. Palmer)

香港大學社會學系、香港人文社會研究所教授

In memoriam Kristofer M. Schipper

Kristofer M. Schipper enshrined at the Xuanmiao guan Daoist temple in Suzhou. Art credit: Huizhentang. Photo credit: Tao Jin via www.daoisms.org

My doctoral mentor, Kristofer Marinus Schipper (1934— 2021) passed away on Feb. 18, 2021.

I met Schipper during my first year of graduate studies in Paris, in 1995–96. I took his Saturday morning seminar at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, in the dusty old Salle Marcel Mauss in a corner of the Sorbonne. Schipper was a legend in Daoist studies, and for most of the year, I followed the seminar trying as best as possible not to be noticed, during the two hours of study of texts of the Daoist Canon, followed by an hour-long lecture on “Chinese ethnopsychiatry,” i.e., religious healing practices in the Chinese and Daoist traditions.

Toward the end of the year, I approached him, asking if I could be his doctoral student. “No. I’m retiring soon, and I’m not taking any new students”. But I insisted, and gave him my masters’ thesis containing my initial findings on the qigong movement in China. The following week, he accepted to be my directeur de thèse.

Kristofer M. Schipper in 2009. Photo credit: Yuan Bingling via nl.wikipedia.com.

As a mentor, Schipper was strict and intimidating. I felt out of place among the students in his seminar, who all worked on Daoism in early historical periods — for them, “modern Daoism” started in the Song dynasty, over a millennium ago! Researching the Qigong movement in the mainland Peoples’ Republic of China, I was the only person who wasn’t studying historical texts, or doing fieldwork on traditional Daoist rituals. I was working on a decidedly contemporary phenomenon, very much a wave of “new religious movements,” a re-invention of elements of Daoist tradition under post-Mao socialism. But Schipper saw this as an important chapter in the contemporary history of Daoism, and he was keen that I write that story.

We were not close, but I deeply respected him, and his influence on my work was profound. I owe him my career, and am immensely grateful to him. The advice he gave me saved me from certain failure, and laid the foundation for the success of my research.

I am an anthropologist by vocation. I wanted to do field research and participant observation, and I was attracted to the French tradition of Claude Lévi-Strauss. Schipper had done ten years of field research among the traditional Daoist masters of Taiwan in the 1960s, leading to his ordination as a Daoist priest. His seminars were dazzling intellectual performances. He would start by sharing photocopies of an obscure text of the Daoist Canon, perhaps from the Han dynasty, and would start reading and commenting. Sometimes, after reading only one or two sentences of the text, his commentary would become an hour-long impromptu digression, unpacking a single term, linking it to other terms in the text and other texts, expounding on its significance, evoking anthropological theories and examples from India or other cultures, touching on contemporary debates and discussions, chanting the text as he had learned in Taiwan.

He was, perhaps, the last true Sinologist: he could speak with authority and deep understanding about virtually any period of Chinese history, from the Warring States to the contemporary period. His mastery of textual study was unsurpassed, as was his years of field research, which took him deep into the popular strata, where, ignored by elite scholars, the Daoist tradition still lived. Almost single-handedly, he founded the academic field of Daoist studies.

Prior to Schipper, only a tiny handful of scholars, in France and Japan, had paid any attention to Daoism. The general consensus was that there was nothing of interest in Daoism, which, in any case, had disappeared. Nobody knew how Daoism was practiced, and nobody knew how to make heads or tails of the 1476 texts — most of which indicated neither author nor date — of the Daoist Canon, of which there were only a handful of copies remaining. Through his academic “discovery” in the field of southern Taiwan, he showed that Daoism still lived among the people. His students, followed by many other scholars, have continued since then to study how Daoism exists as a lived tradition, rather than as a trope of philosophers or New Agers.

Young Daoist master on his way to his initiation in the Zhengyi order, in Gangshan, Taiwan, 1963. Photo credit: Kristofer Schipper, 1963 via Wikimedia Commons.

Following his time in the field, his main life’s work was in his leading an international team that conducted the first ever systematic study of the Daoist Canon. The textual tradition was given legibility, clarity, and dignity through the work of Schipper and his team. After the Handbook on the Daoist Canon was published in 2005, the foundation of the field of Daoist studies was established.

Kristofer Schipper and Franciscus Verellen eds., The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

There was a connection, though, between Schipper’s textual work, which was inevitably historical, situating texts in their historical context, and his field work: Daoism in the field is primarily a ritual tradition; and most of the texts in the Canon are ritual texts. No matter how Daoism is approached, taught Schipper, embodied ritual practice is the key. The embodiment is both individual and social. This unified approach transpires in Schipper’s masterpiece, The Taoist Body. The narrative starts with the festivals of the people, and ends with the mystic flights of Zhuangzi. Chapter by chapter, the book advances seamlessly, in a steady progression, from the practices of the common people, to the training of the Daoist masters, to the cultivation of the body, and to the realms of the Immortals. Most accounts of Daoism treat these dimensions as distinct fragments, focusing on one to the exclusion of the others. But the Taoist Body takes the reader on an initiatory journey. The connections between the chapters reveal as much as the content of each. Yes, it’s an academic work — still unsurpassed as an introduction to Daoism, since its first publication in 1982. But it’s so much more than an academic work.

Kristofer M. Schipper, The Daoist Body. University of California Press, 1993.

Read it again. And again. The book is alive. The Daoist body is a living, immortal body. Not just the individual body, but the social body. The social body of Daoism is a living body. And this is, to me, the most important lesson to be gained from Schipper.

Regrettably, he never published a detailed ethnographic account of his field research in Taiwan. But he took into himself the life of the Daoist lineage and community he studied — and through him, and his passion, the texts he taught, the histories he narrated come to life.

Contemporary academic paradigms love fragments and detest essences. These paradigms would lead us to question whether something called Daoism really exists. Schipper was no peddler of a simplistic Daoist holism. He was rigorously empirical, historically minded, attentive to difference. But for him, the priests at the Emperor’s court, the masters and mediums in the remote villages, the Celestial Master ritualists, or the Western Tai Chi practitioners — all are expressions of a single living Daoist tradition. And, he never ceased to insist, this tradition is the true body of China — its zhuti. This was the controversial proposition he put forward.

Step by step, piece by piece, he and his students, and the growing community of Daoist studies, through their research, have given flesh and life to this account of China’s Daoist body, and to its centrality in China’s history, from ancient times until the present. This is China’s yin body — the body of the lowly people in the shadows, the invisible, overlooked source of China’s life — in counterpoint and resonance with China’s yang body draped in a Confucian and, later, Socialist robe. This is the path, the Dao of Daoist studies that Kristofer Schipper called on us to follow.

* * *

My research team at the University of Hong Kong’s Yao Dao Project, have decided to dedicate our project to the memory of Kristofer M. Schipper. We hope that our research can fully exemplify the conjunction of textual and anthropological research, attentive to the conjunction of Daoist and local cultures. For more information, see here:

Yao Dao Project

The Yao Dao Project has conducted systematic anthropological research through participant observation on the culture…

yaodaoproject.com

Please see below for interviews of Kristofer Schipper, filmed at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2007 as part of a conference on Religion and Chinese Society that I co-organized with Vincent Goossaert and Peter Ng, and as part of the audio-visual component of the Chinese Religious Life book and website project:

Click here for my review (in English) of Schipper’s book The Religion of China: The Living Tradition, a compilation of his most important and influential articles, published in French in 2011.

Click here for Schipper’s foreword to the volume Daoism in the Twentieth Century: Between Eternity and Modernity (University of California Press, 2012) which I co-edited with Xun Liu.

Click here for a description and photos of a memorial service held for Schipper at the Xuanmiaoguan Daoist temple in Suzhou.

See below for a commemorative event held online by the Society for the Study of Chinese Religions, featuring eulogies by leading scholars, collaborators and students of Schipper:

相關鏈接

施舟人教授道教研究論著選目:https://www.douban.com/group/topic/213022477/

更多資訊請點擊:https://www.douban.com/group/histoireligio/